Abstract

Dense seismometer arrays offer new opportunities for exploring delicate near-surface near-fault structures. By integrating regional dense seismic array data, seismologists’ understanding of fault systems has rapidly improved in the past decade. However, obtaining a high-resolution shear wave velocity structure is still challenging, especially for complex near-fault systems. In this work, we apply the recently developed array-based multimodal surface wave tomography method (the frequency-Bessel transform method, abbreviated as the F-J method) (Wang et al., 2019) to image complex subsurface systems. This method provides dispersion curves with a broader frequency band, enhanced resolution, and overtone extraction. However, limited by the subarray selection for three-dimensional imaging, integrating the F-J method into complex structures needs a more reliable workflow. We propose the “partition similarity test” method (FJ-PST) to adaptively and quantitatively find suitable subarrays to address the partition challenge adaptively by testing larger subarrays with smaller ones based on the dispersion similarity.

An Issue of Partition

A critical assumption of the F-J method:

The F-J method utilizes a Bessel function integration to reveal the dispersion spectrogram (\(I(\omega,k)\)) from the CCFs in the frequency domain (\(C(\omega,k)\)):

\[I(\omega,k) = \int_0^{+\infty}C(\omega,k)\cdot J_0(kr)rdr\tag{1}\]Where \(\omega\) is the angular frequency, r is the epicentral distance, k is the wavenumber, and \(J_0(kr)\) is the first kind of zeroth-order Bessel function. The dispersion curves can be estimated from the local maximum of the dispersion spectrogram. In addition to the fundamental mode, it can effectively retrieve overtone dispersion curves (Wang et al., 2019) and even leaking modes (Li et al., 2021). However, as an array-based method, it assumes that the coverage of a subarray has a layered velocity structure .

What happened if the subarry has a non-layered structure?

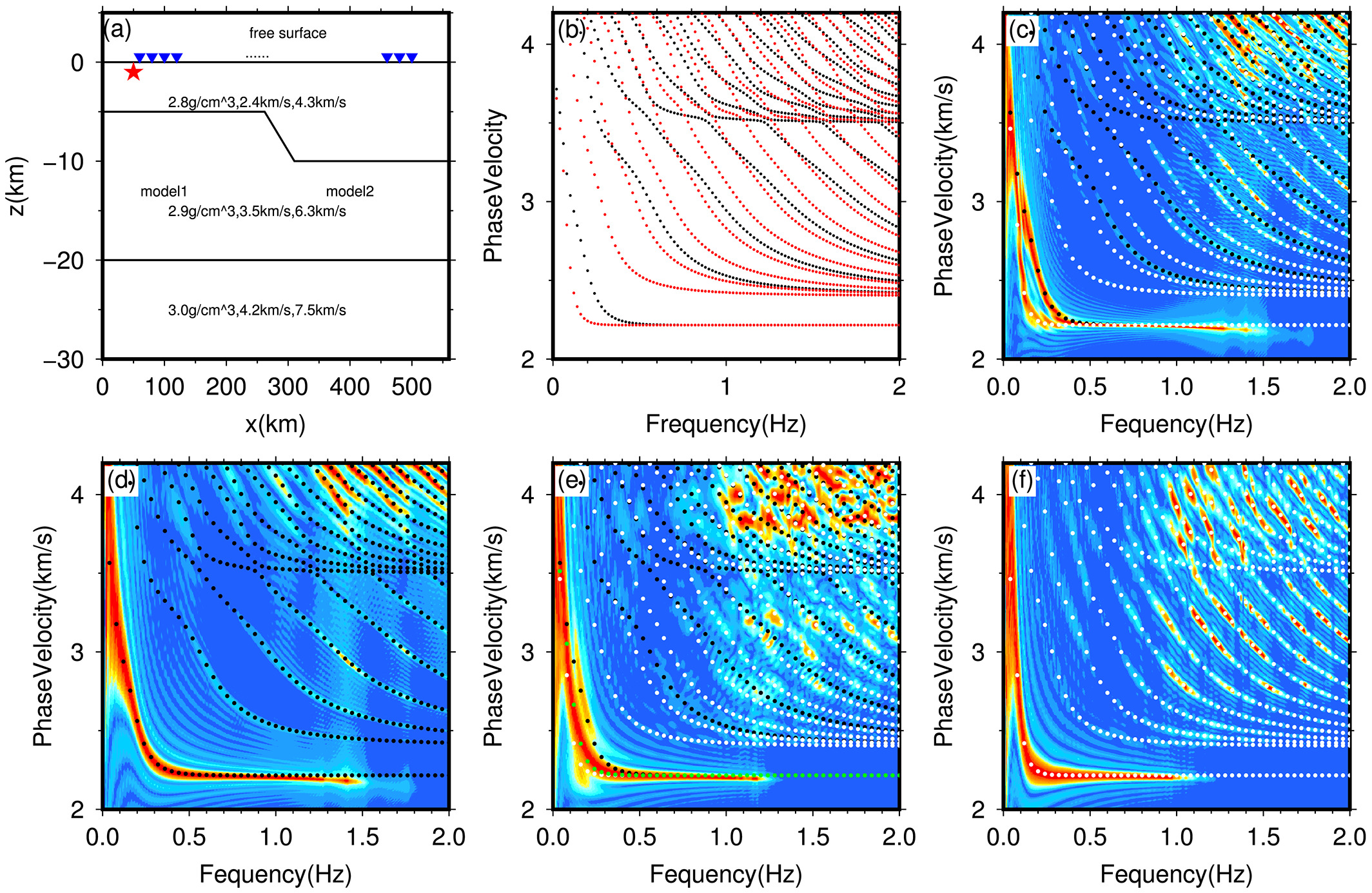

The traditional partitioning method tests various sizes of regular shapes, such as circular or square partitions, to identify suitable configurations and employs moving windows to indiscriminately cover the array. While this approach can be effective in large-scale lithospheric tomography, it presents challenges for imaging complex structures. As noted in previous synthetic work (Li & Chen, 2020) (Figure 1), the dispersion spectrogram obtained using the F-J method bifurcates into different structures’ dispersion patterns when subjected to drastic velocity variations. Therefore, irregular-shaped subarrays are necessary to avoid crossing these areas. Although irregular-shaped partitions can be manually tested and selected, this significantly increases the workload.

Partition Similarity Test

To address the previously mentioned problem, we aim to develop a quantitative measure for adaptively selecting suitable irregular-shaped partitions. In this study, the proposed measurement is based on the similarity of dispersion curves.

Criteria of similarity between two dispersion curves:

To objectively evaluate dispersion curves’ similarity, a relative error (RE) is defined as follows:

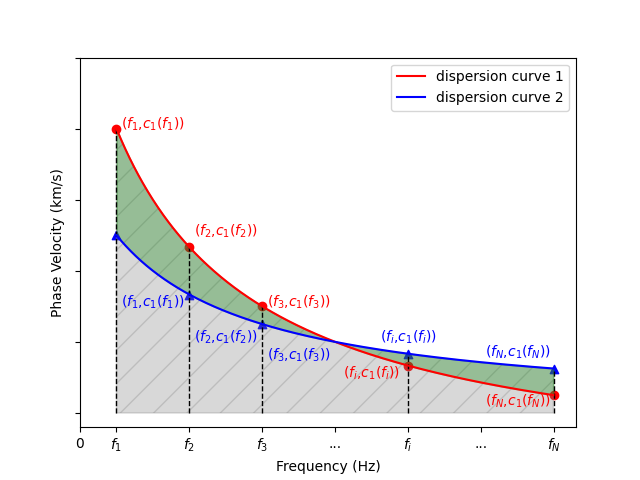

\[e_{12} = \frac{\sum_{i=1}^{N} \left|c_1(f_i)-c_2(f_i)\right|}{\sum_{i=1}^{N}max[c_1(f_i),c_2(f_i)]}\tag{2})\]Where \(f_1\) to \(f_N\) represent the N picked frequency points for two dispersion curves, while \(c_1 (f_i)\) and \(c_2 (f_i)\) represent the corresponding phase velocity at \(f_i\). Figure 2 illustrates this design.

Workflow of the Partition Similarity Test:

The partition similarity test (PST) assesses the homogeneity within a subarray and eliminates stations producing dissimilar dispersion curves to form a new one. The workflow consists of four steps:

-

Firstly, the size of “targets” and “probes” should be set (refer to Figure 3). A “target” represents a sizeable regular-shaped subarray, and “probes” are those smaller subarrays used to evaluate targets. The target size depends on the aimed dispersion frequency band, whereas the probe size depends on where the target’s dispersion spectrogram bifurcates. All possible targets and probes are generated to thoroughly utilize the data and enhance lateral resolution, as shown in Figure 2.

-

Secondly, the RE of each probe is calculated within each target by the previous measurement. At this step, all other probes’ dispersion curves RE are calculated with the one nearest to the target centroid.

-

Thirdly, the error threshold is set, and the remaining probes are combined. Determining an appropriate and unbiased threshold requires further research. It could be empirically set as 0.05. Subsequently, new subarrays will be generated by combining each target’s remaining probes.

-

Finally, quality control is performed to remove unsatisfactory partitions. In transition zones, probes may still exhibit bifurcation in their dispersion spectrogram, resulting in accepting few or disconnected probes. These new partitions can still not accurately estimate their centroid velocity. Therefore, only subarrays generated by more than four adjacent probes will be used.

Comparison to F-J

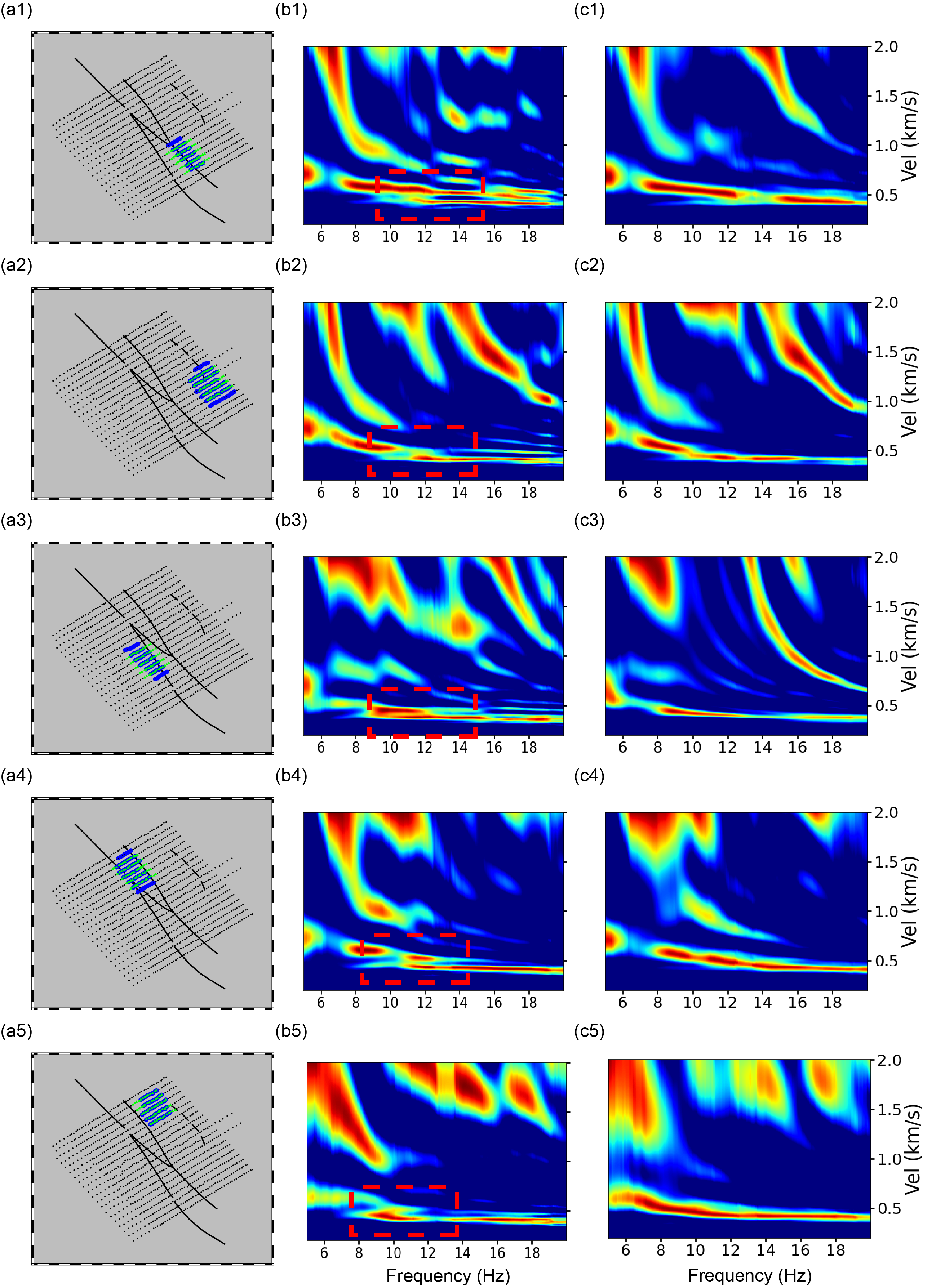

Here, we demonstrate the effectiveness of the FJ-PST by comparing it to the dispersion spectrogram calculated by the traditional F-J method in a dense nodal array deplyed at San Jacinto Fault Zone (Ben-Zion et al., 2015). As indicated in Figure 4, the entire array suffered from extensive and severe fundamental mode bifurcation on the dispersion spectrogram calculated by the traditional F-J method, while the FJ-PST successfully detected the boundaries and adaptively adjusted the subarrays to mitigate this issue.

Applications

High-resolution Fault-Zone Tomography

- Related Project: Complex Fault Tomography Using FJ-PST (San Jacinto Fault Zone)